|

2023 Highlights:

Check out the full 2023 Impact Report available on our website!

0 Comments

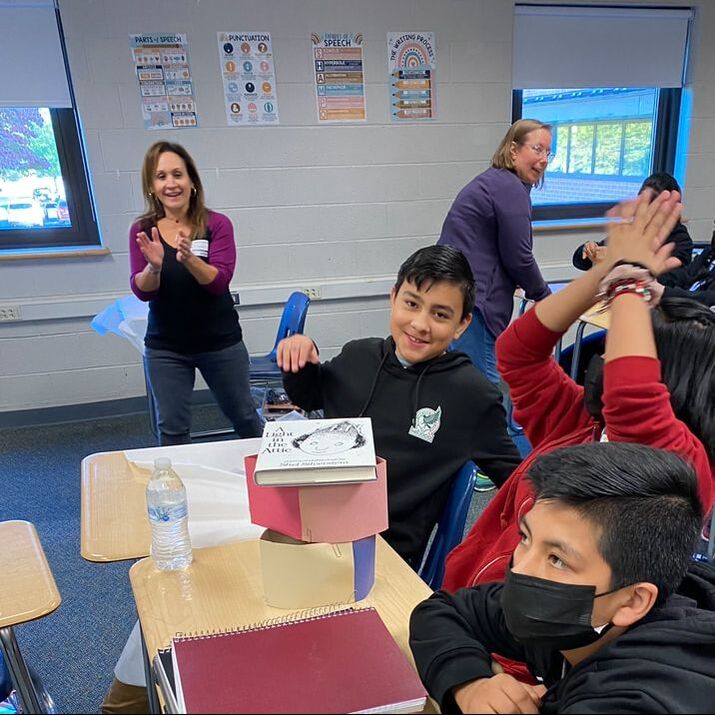

"I finally found a partner who really understood what my students needed" In PROJECT LIBERTAD1/9/2024 by Christine Gartner, Board Vice President for Project Libertad and English Language Development teacher, Norristown Area School District, [email protected] Teaching students English who speak another language at home has been my passion for over 20 years! Watching my students blossom from shy and unsure into fully integrated students in the school’s culture is really rewarding and something to see. I enjoy sharing not only their new language, but also our culture and their part in it. Students bring their knowledge, culture, dreams, and often - trauma - to their new school. Teachers need a variety of skills and strategies to assist their students. It is the responsibility of schools to ease the transition and assist in their learning. However, I have found over the years that schools do not have the right tools to reach our new ELD (English Language Development) students in very subtle ways. Specifically, I have experienced frustrations in helping my students in the areas of mental health and social issues. For years, I struggled with finding help for my students and their families but often ran into challenges in inability to access certain resources or a huge waiting line while my student needed immediate help. Many organizations had no language assistance or knowledge of new immigrants and their needs. Often I was turned away and told they didn’t know where else to suggest to connect in our community. When Project Libertad came to my school, I finally found a partner who really understood what my students needed! New immigrants have their own very specific needs as students and often general resources can’t address these needs. Project Libertad can provide what school districts just can’t for many reasons. Now, they are my partner for mental health, a weekly club where students have their own community, and access to resources that are specific to immigrant youth and their families. There is no other organization in our area right now that can provide what my students need! We have come to depend on Project Libertad to support our new students and have seen incredible gains since our partnership began.

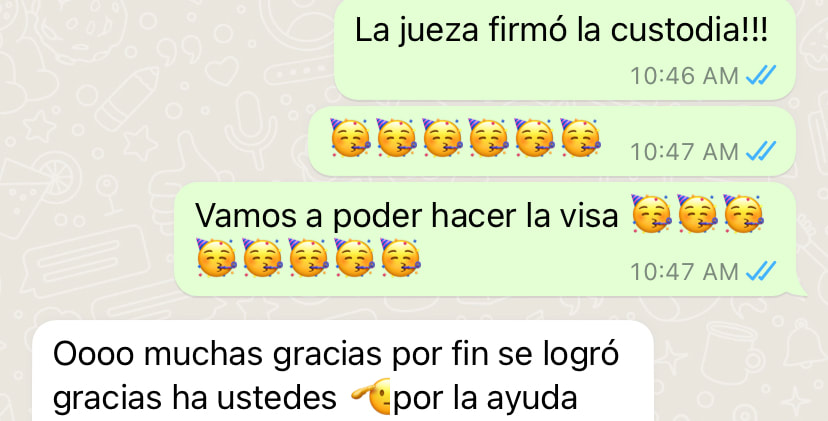

In addition, the Professional Development training for teachers has expanded knowledge with the staff that also have interactions with my students. This has not only aided my job frustrations, but also expanded something even more incredible - more allies for our students to rely on when the teachers are taught what new immigrant students need and where they come from. Teachers have reported to me a new level of empathy when they attended a professional development session with Project Libertad - specifically a deeper understanding of common traumas that our students experience and strategies gained on how to assist them. Again, there has been no other training like this that is specific to our students in our area. We need this partnership in order to serve our new students and their families in the most respectful and supportive ways. Project Libertad has provided for the needs I have been searching for and I value our partnership. Finally, I found an organization that understands my students, their families and provides support. I was so impressed that when I was offered a chance to help I said “yes”! I joined the Board and have been part of an incredible team that is ensuring the future with Project Libertad. Interested? Come join us! Contact us and see how you can help my students and me! We will find the right fit for you. by Olivia Knight, MAS, Juntos para Jóvenes/United for Youth Case Manager Today I want to share a heartwarming story of a student whose custody hearing I observed in person. I started working with the student last year, when I first began working at Project Libertad as a case manager. This particular client was an excellent student during her first year of school in the United States, and she had received almost all As, despite the fact that none of the teachers at school spoke her first language, an indigenous language. Things changed during her second year, and I still remember the first messages we exchanged, in which she told me about her pregnancy. She was scared and unsure of how to proceed. She had a lot of absences from school, and when her baby was born in the spring, she left school due to a lack of childcare. We knew that she had a track record of academic excellence, and we also knew that school attendance would be an important factor in obtaining Special Immigrant Juvenile Status. So, at Project Libertad, we strongly advocated for her. We helped her reach out to a custody lawyer who was willing to take her case and worked closely with her on it. We connected with her teachers and high school administrators, who created a personalized path for her to continue school online. We arranged for a social worker to evaluate past trauma, to help explain why she left her home country, and why she missed so much school. And finally, we connected with her father, who is her caregiver and was instrumental in providing all the resources she needed to be successful.

Thanks to all of these efforts and collaborations, we obtained the custody order required for her immigration case, and her Special Immigrant Juvenile Status application was filed this week! Learn more about Olivia's work here. by Rogelio Ayllon, Board President Recently, I had the opportunity to help Rachel, our Executive Director, with legal intakes for middle school students in one of the school districts we serve. It was an opportunity to see our work on the ground and meet many of the youth that we serve. The legal intake process was tough — it was difficult to not sound shocked or emotional as the youth shared their stories. As a board member, I am generally removed from the day-to-day operations, so getting to experience our daily work helped me appreciate even more the work that our staff and volunteers do day in and day out. It is not easy work, and yet our volunteers choose to help because they believe in the importance of what we do. In many ways, this experience also amplified my belief in Project Libertad’s mission and why our work is so critically important. I spoke to a newcomer who had endured a brutal 3-month trip to the United States with his family, exposed to life-threatening situations to seek protection. Throughout his trip, they crossed two borders, saw friends die along the way, were threatened by various people, went hungry, and slept on the pavement as they awaited processing into the US. Immigration has a multifaceted impact on children’s lives. On top of not being entitled to legal representation through the immigration process, the arduous trip to seek entrance into the US takes a toll on their physical and mental health. When they are successfully admitted, they often face financial insecurity and are vulnerable to abuse due to their status.

At Project Libertad, we aim to bridge that gap by providing legal, educational, and mental health programs for immigrant youth. The support that we get from donors, advocates, and volunteers goes a long way to ensure that we meet the needs of these children. Every donation, whether it’s $5 or $1,000, allows us to help more youth like the ones I met recently. I hope you’ll help us make an impact. Please consider donating or volunteering! Rogelio by Olivia Knight, MAS, Case Manager Hi everyone! I recently went through the process of transferring my case records to a different tracking system, and in the process I learned a few things about what I have accomplished since last October, when I started working at Project Libertad.

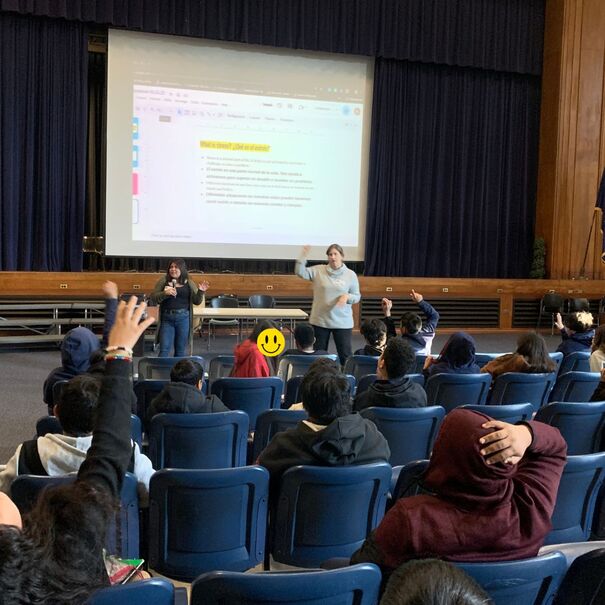

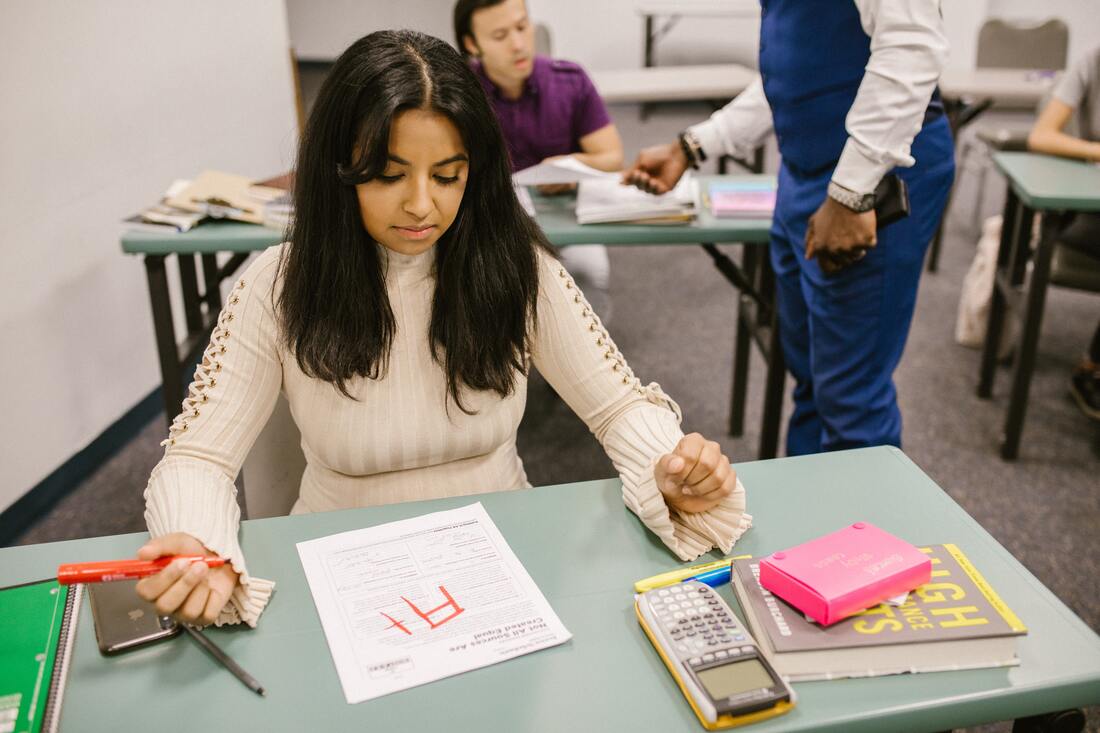

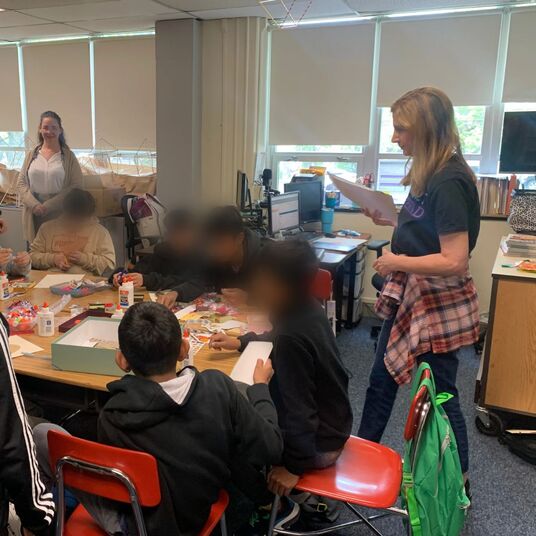

I spend a great deal of time working with clients applying for something called Special Immigrant Juvenile Status (SIJS), which you can read more about in this blog post. SIJS is a type of immigration status for children who have been abused, abandoned, or neglected by a parent. The first step in an SIJS case is to obtain a state court order (usually through custody or dependency proceedings) with special findings related to SIJS. My role is to work with our legal team on these cases by connecting students to custody lawyers, helping them turn in the necessary records and paperwork, and supporting them through any academic deficiencies. In certain counties, this is often a frustrating process for children hoping to apply for SIJS. Some courts can be very particular about educational success as a prerequisite for custody. In some cases, a judge will not sign a custody order unless the caretaker is working closely with the child to ensure sufficient academic progress. Grades and school attendance records are everything. So, you can end up with situations where the child has strong facts that qualify them for SIJS (meaning clear abuse, abandonment, or neglect by a parent), but they are unable to obtain the required custody order due to academic challenges. Without that custody order, they are not eligible for SIJS. Trauma causes many of our clients to struggle with school attendance and grades. One study found that, “Two-thirds of [migrant] youth experienced at least one traumatic event [during migration], 44% experienced an event once, and 23% experienced two or more traumatic events during migration.” “Traumatized students are in every single classroom, every day—no matter the grade or subject…For these youth, navigating life, even in the safety of your classroom, can be challenging. Seemingly commonplace occurrences and routines can actually become classroom trauma triggers that cause a domino effect of negative reactions. And once triggered, a traumatized student can’t be engaged in your lesson, and their learning stops.” -- We Are Teachers My journey to transfer case records began with my belief that I was about to uncover a long list of students for whom I’d been instrumental in obtaining custody orders. But when I counted them up, I realized there were just four, with six more on the “in process” list. The amount of time it has taken to help just four students in the first step of their SIJS cases was pretty shocking. But when I look back on all the systems that need to come together to coordinate a successful custody case—individual families, schools, private lawyers, and the judicial system—it is not so shocking. Each system has idiosyncrasies that make it challenging to work with. Caretakers work long days, schools are overwhelmed, private lawyers have specific office hours, and the judicial system is rigid. One factor that makes a huge impact is having counselors, teachers, and other school staff who not only understand trauma but implement proven strategies to better support students living with trauma. With perseverance and the right amount of advocacy and creativity, we at Project Libertad are here to help children win their cases, remain in the United States, and achieve the best possible outcomes. by Lauren Dunoff, Newcomer Support Program Coordinator My day begins with planning and preparing materials for this week's Newcomer Support Programs and sharing the lesson plans with the teachers and volunteers. I also correspond about some other fun upcoming things at Project Libertad, including our evening at a Philadelphia Union soccer game and inviting visitors to our summer camp program. I then load my car with materials and drive to this afternoon's classes at Phoenixville Area High School. There, I meet our volunteer Courtney. We will see just over 30 students today, from countries including Guatemala, Mexico, Honduras, El Salvador, and Thailand. Our activities today include making candy sushi, bird feeders, and a traditional Mexican craft called Ojo de Dios (Eye of God). We will also review some English language vocabulary about Spring. The candy sushi activity is a big hit, and the students participate well with the vocabulary. The art projects take a little more persuading, especially in our all-boys' Healthy Masculinity Program. In the end, each student has made an Ojo de Dios and seems happy about it. The highlights of my day include catching up with a student from last year's RISE girls' program who is now a junior, and I’m happy to hear she’s doing well. I also had a great conversation with one of our ninth-grade boys. He asked me why he has to take all of these classes, like English, Math, and Chemistry, when that isn't what he wants to do for a career. We discussed the ways education and learning English can benefit his future. With three more years of high school ahead for him with his caring teachers and mentors, I anticipate he will do well.

Opportunities to connect with the students in a positive way like this happen every day, and that is the best part of this job for me. I learn so much from the teachers I meet, as well as from the students. Being able to connect with and relate to people who grew up in cultures different from mine is a wonderful feeling. It motivates me to continue to learn Spanish, strive to listen to others, and have more meaningful conversations. I am truly grateful to know the students of Project Libertad and grow from these experiences. by Olivia Knight, MAS Olivia is a Case Manager in the Juntos para Jóvenes Project, where she connects immigrant youth in Montgomery County with social services. Over the past six months that I have worked at Project Libertad, I have witnessed no less than six instances of barriers to medical care experienced by my clients. In some cases, these barriers were among those common and familiar to the entire immigrant community: a few examples include financial limitations, lack of insurance, language struggles, and health literacy. But one barrier has stood out as uniquely troublesome for newcomer immigrant youth who are unaccompanied. The experience of being a minor without a legal caregiver trying to navigate a complex web of private health systems, nonprofit clinics, confusing confidentiality laws, and rules about who can bring a minor to the hospital makes it–at times–impossible for our clients to receive medical care. It is so important to the Pennsylvania government for children to receive healthcare that all citizen children who aren’t already on their parents’ insurance plans are eligible for Medical Assistance or the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP). But the reality is much harsher for unaccompanied children. Not only can they not qualify for health insurance until they have a pending legal case; they also cannot present at a doctor’s office or the emergency room without an adult caregiver. Because unaccompanied children have, by definition, arrived in the United States without their parents, they are often placed with a family member or adult family friend. These caregivers are designated by the Office of Refugee Resettlement, but they have no legal standing with medical establishments. This inability of the medical system to incorporate unaccompanied children is the reason I have received phone calls from doctors’ offices asking me if my clients’ caregivers were really relatives or friends. It is the reason my client could not be seen for a serious medical issue without an accompanying parent. And it is the reason I was told I could be reported by emergency room staff last fall for bringing my client there. The New York Times recently reported on the increasing number of unaccompanied children working in dangerous roles in violation of child labor laws. If we are incorporating newcomer immigrant youth into the workplace, we need to figure out how to incorporate them into healthcare settings. The burden should not fall on the children themselves.

Teamwork Makes The Dream Work: Why Collaboration is Crucial for SUpporting Immigrant Youth4/27/2023 by Rachel Rutter, Esq. and Olivia Knight, MAS Rachel met a client we’ll call Maria in the summer of 2021, when one of her teachers referred her to Project Libertad for immigration legal services.

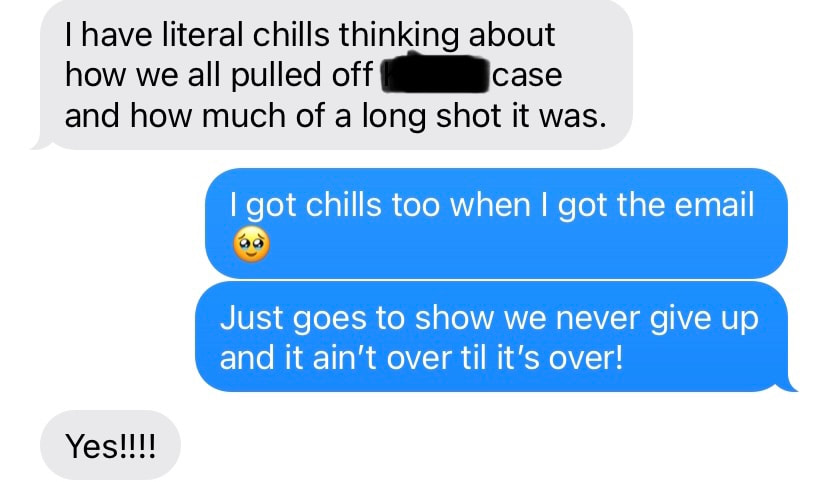

At the time, the legal case seemed straightforward: Maria was eligible for something called Special Immigrant Juvenile Status (SIJS). SIJS is a path to legal immigration status for children who have been abused, abandoned, or neglected by a parent. To qualify for SIJS, a child must either be placed in someone’s legal custody or adjudicated dependent on the state (for example, placed in foster care). Generally speaking, the state court has to find and explicitly state the following in its order for the child to qualify for SIJS:

The next step in Maria’s case, then, was for Maria’s caregiver to obtain legal custody of her in family court. The path seemed simple and straightforward, but it turned out to be anything but. First, financial difficulties prevented Maria and her sister from moving forward with the custody process. In response, Rachel helped them to find a nonprofit organization to take the case. Next, that nonprofit organization unexpectedly dropped the case, because they were fearful of how the custody judge would respond to Maria’s poor grades and school attendance. The particular custody judge in this county refuses to sign custody orders for kids with poor grades or attendance. Educational system support is a big part of what Olivia strives to bring to her clients, not just because the youth Project Libertad works with often struggle in their English-only classes, but also because their academic performance in school can affect their legal cases in such a profound way. In custody court, the children’s grades and school attendance are closely examined, with the assumption that these records are a reflection of the caregivers’ dedication to education. This nuanced feature of the SIJS process in our area is one of the most poignant reasons why it is important for lawyers and case managers to work together. The clock was ticking, with just weeks left before the child’s 18th birthday, when she would age out of her opportunity to pursue SIJS. Rachel and Olivia worked tirelessly to find a lawyer who would take a chance on this deserving client. Most lawyers we approached were not interested in taking a case that seemed so dire. It was also a struggle to connect with the client and her caregiver and gain their buy-in, because they felt understandably discouraged and hopeless about their possibilities for winning a custody hearing. Finally, after several more rejections by attorneys and clinics, Rachel and Olivia found a local custody attorney who agreed this child was worth fighting for. Next, Rachel and Olivia worked with our partner organization Immigrant Psychology Network to give our client the best possible chance of success. Dr. Susanna Francies leapt into action on short notice to provide a psychological evaluation for the client. Dr. Francies was able to connect the client's prior trauma to her academic issues and connect her to mental health supports moving forward. Thanks to Dr. Francies and IPN, the judge was sympathetic to the plight of our client. All of these forces combined to result in the greatest possible outcome for our client: the judge signed the custody order, complete with all of the SIJS findings! Thanks to this teamwork -- a labor of love by lawyers, social workers, and mental health professionals working collaboratively -- our client will be able to apply for SIJS and remain lawfully in the United States. She will also have the mental health and social support needed to ensure her future health and happiness. Hi everyone! I want to share an experience I had taking a client to the emergency room several weeks ago. The client had been having medical issues for about a month that were not resolving. We had taken them to Urgent Care two times, each time with the same answer: “the patient needs to see a specialist.” Without insurance, the client had no ability to pay for a specialist, and as an unaccompanied minor, there was no steadfast adult in their life who could bring them to medical appointments. The unfortunate fact for many of our clients is that when they have health issues, they are too young to present themselves to medical facilities alone. This can lead to ongoing, unresolved problems like the one this client was experiencing. After calling around to several organizations involved in the case, the responsibility fell to us at Project Libertad to bring the client to the hospital. When we arrived, we approached a window where we were asked to register. There was immediate confusion over who would pay the client’s medical bills, and since I was unrelated to the client, there were also questions about who I was and why I was bringing a minor unrelated to me to the hospital. Once we finally reached a non-present family member who was willing to provide their information over the phone, and once I presented work identification, they allowed us to enter the waiting room. In the examination room, there were no medical professionals who spoke Spanish, so I became the de facto translator. A medical student came in to ask questions, followed by a nurse who took the client’s vitals. After plenty of waiting, a doctor spent less than five minutes examining the client and diagnosing their medical condition. After our trip to the emergency room, we picked up some medication at the pharmacy, where we spent another hour waiting and where we paid nearly $50 even with the pharmacy discount. In contrast, later that week, I took my own son to the emergency room. We had insurance for him, and as his parents, we were the ones who brought him there. We presented our identification at the hospital and there was no question over who we were and who would pay his bills. The doctor spent a total of 15 minutes with us explaining his medical situation, and several different tests were ordered to rule out more serious complications. And I know that when the bill comes, our family will be able to afford it because he has medical insurance that adequately covers his care. This story is not just about one client. It’s about the experience of being a young, newcomer immigrant in the United States without parents or supportive caregivers. Project Libertad exists to fill gaps for these young people fleeing violence or abuse in their home countries, who still have the same problems as every kid when they arrive in the United States, even if they don’t have caregivers equipped to fully support them. My official role may be Case Manager, but advocating for my client in the hospital that day felt a lot like donning several different hats simultaneously, which is what I do every day as a parent. by Justin Mixon, Esq. I don’t have time to write this. Immigration lawyers like me around the country don’t have time. For those of us representing immigrant families who have arrived in the US in the last 8 to 10 years seeking asylum from violence and persecution, with those families still fighting their cases in immigration court, what we have is an obligation to keep families here at all costs and prevent deportation. On April 3, 2022, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) published guidance to the attorneys representing DHS. The guidance instructs DHS attorneys to use Prosecutorial Discretion to dismiss thousands of cases, mostly asylum cases, in immigration court, prioritizing for dismissal immigrants who crossed the border before November 1, 2020, and who are not a threat to national security or public safety. The Biden Administration wants to decrease the “backlog” of cases to make room in the system for people who may enter in the next few months. The American Immigration Lawyers Association recently estimated that there are about 700,000 low or non-priority cases in the current immigration court “backlog.” Sounds good on the face of it, but the devil is in the details. Here’s the problem – the Biden administration has decided that it is better to dismiss or terminate the low priority cases and leave immigrants in the US WITHOUT work permits or social security numbers. In other words, they will stay here, but become part of the underground economy. People who have had work permits for 6-8 years while they wait for a decision in their asylum or other immigration court case will lose work permits. When an immigrant loses their work permit, they also lose access to a driver’s license, their ability to pay taxes, register their children for college and complete the FAFSA for student loan eligibility. They will be vulnerable to unscrupulous employers, consumer fraud, and criminals who see them as defenseless without “papers.” What makes this decision to take away work permits even more unconscionable is that there is a ready-made solution that worked just fine during the Obama Administration. It is called Administrative Closure. An immigrant whose case is administratively closed continues to have their case in the immigration court, but with no future hearing date. The case is removed from the court’s active workload. The TRAC research center of Syracuse University calculated 69,355 immigration court cases closed using Administrative Closure as a form of Prosecutorial Discretion between 2012 and 2017. To no one’s surprise, the program ended with the Trump Administration. In December 2021, DHS Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas stated that he did not favor Administrative Closure. He wanted cases dismissed outright so that they would be permanently off the court’s docket. Mayorkas has no authority over the immigration courts; they are part of the Department of Justice. DHS does have to maintain and store the files for Administratively Closed cases, but it is hard to imagine this creates any significant hardship. So, when DHS’s Principal Legal Advisor (OPLA) Chief Kerry Doyle published guidance strongly favoring dismissal instead of Administrative Closure, she was following her boss’s lead. In an engagement webinar with immigration attorneys on April 5, 2022, she commented that the problem of work permits is “not in our lane.” Apparently, the top priority for President Biden’s DHS team is to close cases at all costs. The Biden administration seems more concerned about counting beans, decreasing the official “backlog” of 700,000 cases, than the real cost in human terms. It would have been easy for the Biden administration to explain to press outlets and the public that administratively closed cases do not count as part of the immigration court “backlog” since they are not active cases. It would have been easy to avoid telling immigrants they must hide in the shadows again and can’t renew a work permit or have a social security number. Now, the Biden administration wants me to be a part of their “solution.” They want me to encourage my clients not to object when the government asks to dismiss the case (DHS retains the right to dismiss cases even against the request of the immigrant, and it may come to that). Now, I must explain the pros and cons of dismissal to my clients, or at least try to explain. Dismissal will save them from the immediate threat of deportation, but it does not grant them any status. They will lose their work permits and go into the shadows with the other approximately 11 million undocumented immigrants in the US. It will be hard for them to see this as anything other than a significant step backwards. Welcome to America. Justin Mixon is an immigration and family law attorney in Jenkintown, PA.

|

AuthorSArchives

February 2024

Categories |

- Home

- About

- Donate

-

Programs

- Immigrant Children's Defense Project

- Know Your Rights Project

- Conexiones or Connections Therapy Program

- Legal-Mental Health Partnership

- Newcomer Support Programs

- RISE: Refugee and Immigrant Students Excelling

- Mentoring Program

- Juntos para Jóvenes: United for Youth

- Jóvenes Fuertes: Strong Youth

- Educator Trainings

- Adult ESL

- Scholarship

- Volunteer

- Media

- Contact

- Our Team

RSS Feed

RSS Feed