|

by Ian Garvin Many LGBT+ people leave their home countries in Latin America to seek refuge in the United States. LGBT+ people are commonly discriminated against in Latin American countries, and hundreds of people die every year in Latin America due to anti-LGBT+ violence. El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras, also known as the Northern Triangle, are extremely dangerous areas for LGBT+ people, causing many to flee those countries. While same-sex marriage is legal in the Northern Triangle, gang violence is very prominent, and gangs in those countries target LGBT+ people specifically. A transgender Project Libertad client, whose name is being withheld to protect his privacy, attested to gangs in El Salvador specifically targeting LGBT+ people. According to our client, if members of a gang knew you were LGBT+, they would bully you, and the gangs made their members kill any gay relatives they may have. There are also issues with police discriminating against LGBT+ people and preventing them from being able to report crimes. In El Salvador, according to our client, if you are gay and something happens to you, the police will not investigate. If you attempt to press charges, they will refuse to investigate. Safety for LGBT+ people is a serious issue in Central America, which means that we need to protect LGBT+ people seeking asylum in the United States. Persecution for LGBT+ people starts at a young age in Central America. For example, our client shared that as a child, he was told that spending too much time with another child or eating certain foods made you gay. Professors and schools would persecute any students they believed to be gay, including asking children if they identify as a man or a woman in front of the whole class, which is very traumatizing for a young child. Governments in Latin America are largely ignoring issues of discrimination and protections for LGBT+ people, leading to many being forced into situations where leaving home is necessary. Our client left his home in El Salvador at a young age to come to the United States, as many LGBT+ people do. Leaving for him was not easy, as he had to leave his family behind. Unlike many LGBT+ people seeking asylum, our client was able to enter the United States and receive help from Project Libertad. LGBT+ people are not recognized as needing international protections and as such often suffer violent crimes on their migration journey, as well as suffering pushback when they arrive. The Trump Administration increased restrictions for asylum seekers since 2016 including LBGT+ asylum seekers, forcing many LGBT+ and other marginalized groups to return to conditions identical to the ones they attempted to escape. Since the transition of leadership in the United States, little has been done to remove the restrictions established by the Trump Administration, especially for Central American asylum seekers. There are also no additional protections specifically for LGBT+ immigrants or immigrants from other marginalized groups that are known to experience higher levels of discriminatory violence. There needs to be more recognition for LGBT+ immigrants, as there are almost no protections for them in most Latin American countries, which forces them to leave for their safety. However, there is also no guarantee of safety in coming to the United States. Our client believes that life is better for him in the United States, as people do not treat you differently for being LGBT+, and he wants other LGBT+ immigrants to know that you should not feel guilty to flee to the United States, as in the United States you can be who you are.

I would like to thank our client for his insight on life as an LGBT+ immigrant, and encourage readers to support Project Libertad, as with your support we are able to help clients like him to be their true selves.

0 Comments

Three concrete ways you can support Ukraine right now:

L’Oréal Paris has awarded Rachel Rutter, the Executive Director of Project Libertad, the prestigious honor of being named one of ten L'Oréal Paris Women of Worth in 2022, an award that recognizes the achievements of non-profit leaders making a profound difference in the lives of others by tackling some of our society’s most pressing issues. Each year, the beauty brand selects these women from across the nation to support through charitable grants, mentorship with its network, and a national platform to spread the word on their important charitable missions. Rachel is being honored for her work to support and empower newcomer immigrant youth! As a recipient, our organization has been awarded $20,000! We are thrilled about this amazing recognition and the grant, which is so critical to our work. In November, our organization will have the opportunity to win an additional $25,000, but we need your help! There will be a public online vote for the L'Oréal Paris Women of Worth National Honoree, November 1 through November 30. Stay tuned – as we will need your support for Project Libertad. In the meantime, to learn more about Rachel, her fellow honorees, and the L’Oréal Paris Women of Worth program, please visit Women of Worth.

Thank you for your continued support! We could not do this important work without incredible supporters like you. We're shouting a huge congratulations to our client Carlos, who became a Legal Permanent Resident this week!

Congratulations to our client Carlos on becoming a Legal Permanent Resident or LPR! This is the legal term for someone with a green card. We are so proud of Carlos and the patience, resilience, and hard work that have gotten him to this point. Carlos's case was truly a labor of love that encompassed multiple nonprofit organizations, lawyers, social workers, and the ongoing support of friends and family in order to get to this point.

Carlos arrived in the US in 2016 as an unaccompanied child, fleeing danger in his home country of Honduras. Carlos was processed through the immigration system as an unaccompanied minor and sent to a youth shelter run by the Office of Refugee Resettlement, before being released to live with a relative in Philadelphia, where he would pursue his immigration case. Our Executive Director Rachel Rutter began representing Carlos in late 2016 through the Immigrant Youth Advocacy Project at HIAS Pennsylvania.

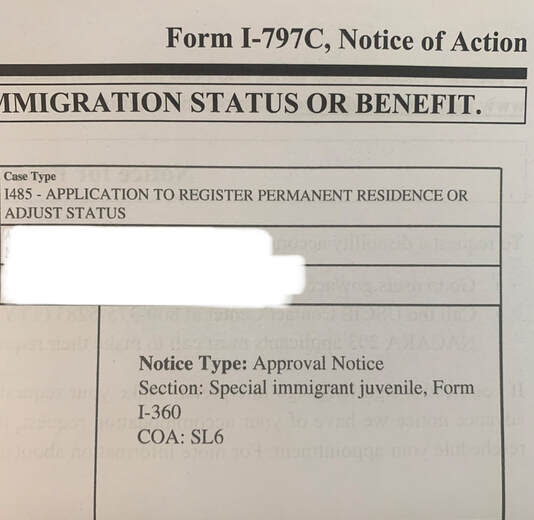

Carlos qualified for a special type of humanitarian immigration status called Special Immigrant Juvenile Status or SIJS -- but there was a catch. Carlos was just weeks away from turning 18 and permanently aging out of this special immigration option for youth. In order to qualify for SIJS, Carlos would need a family court order (like a custody or dependency order) making certain special findings before he turned 18. Thankfully, Jean Strout, a wonderful and accomplished attorney and youth advocate from the Support Center for Child Advocates, stepped up to help Carlos get the court order he needed just in the nick of time. Through SCCA, Carlos also had the support of a social worker, who helped him enroll in school, obtain medical care, and more.

Thanks to Jean's hard work obtaining that court order, Carlos was able to apply for SIJS in March 2017. The SIJS process takes years to complete. After applying, the government often requests more evidence. In Carlos's case, the government requested more evidence and even issued a Notice of Intent to Deny (NOID) the case, even though Carlos had a strong SIJS case. Ultimately, however, Carlos was able to fight the NOID, and his SIJS case was finally approved in December 2018 -- nearly two years after he applied!

However, Carlos's wait did not end there. After a child has approved SIJS, they still do not have any lawful immigration status, as confusing as that may sound. Rather, all that an approved SIJS gives the child is the opportunity to apply for a green card down the road, when it is finally their turn to apply. Whose turn it is to apply is determined through a confusing system called the USCIS visa bulletin.

There is a long backlog of SIJS cases for Central American children, meaning that many kids wait as long as three or four years just to apply for their green card after obtaining SIJS. In the meantime, SIJS kids are stuck in limbo, undocumented, and do not have the ability to work legally or obtain a social security number. Project Libertad has had clients in this situation turn 18 before obtaining their green card and end up being detained by ICE in spite of their approved SIJS. In some areas of the US, it is common for immigration judges to order deportation for these children with approved SIJS, simply because a green card is not yet available for them. It is unconscionable that our inefficient and inhumane immigration system allows this to happen.

When Rachel left HIAS PA to launch the Immigrant Children's Defense Project at Project Libertad in February 2020, she brought Carlos's case with her. Carlos remained in SIJS purgatory. While Carlos awaited his turn to apply for his green card, he dealt patiently and graciously with the various struggles he faced as a result of the SIJS limbo. In October 2020 -- four years after his arrival in the United States -- his turn came, and Carlos applied for his green card. Finally, in August 2021, Carlos's green card was approved!

Thank you, Carlos, for the honor of representing you and watching you handle all of the challenges with grace as you grew from a teenager to a hard-working, caring, and compassionate adult. We can't wait to see what the future holds for you! The brutal police killing of 13-year-old Adam Toledo in Chicago has us reflecting on how much more likely our students are to experience violence than their US Citizen peers, simply because of where they were born and the color of their skin. Immigrant children are much more likely to experience school violence than their non-immigrant peers (Peguero 2008). Newcomers in particular face a heightened risk: first-generation immigrant students are the most likely of all students to feel unsafe at school (Peguero 2008). One study found that immigrant students are “significantly more likely to experience one or more forms of bullying than their U.S.-born counterparts, even after controlling for a number of demographic variables” (Maynard 2016). That same study found that immigrant students are more likely to report being bullied based on “racial/ethnic differences” than their non-immigrant peers (Maynard 2016). Specifically, immigrant children are more likely to report instances of being “kicked, hit, or pushed,” “bullied due to race,” “bullied due to religion,” “bullied by computer/email,” and “bullied by cell phone,” when compared to US-born children (Terzis 2018). The experiences of students who participate Project Libertad’s newcomer after-school programs demonstrate how this anti-immigrant dynamic plays out as school violence locally. Project Libertad’s students, some as young as fifth grade, report physical violence, threats, and intimidation perpetrated against them by other youth because of their race and immigration status. Project Libertad students also report discrimination based on language. Spanish-speaking students report other students bullying them with comments like, “This is America, so speak English!” or “Build the wall!” Both teachers and students report “fight clubs,” in which large groups of students bully and physically attack other vulnerable students. The violence doesn’t end with bullying — Immigrant youth are more likely to face violence and discrimination from police, School Resource Officers (“SROs”), and school security guards than their US-born peers. School security staff may unfairly discriminate against newcomer students due to cultural differences and implicit racial biases. Meant to protect the campus from potential threats, SROs are not supposed to be involved in disciplining students unless an incident rises to the level of a criminal matter (ILRC 2018). However, schools with SROs are likely to have a greater level of law enforcement involvement and arrests of students than schools without SROs (ILRC 2018). Students in policed schools are criminalized for behaviors that may annoy adults but are a typical part of adolescent development; this dynamic can mean that a perceived school rule violation ends up being treated as a crime (ACLU 2017). SROs and security guards lack proper training regarding the unique challenges and cultural backgrounds of newcomer students (ACLU 2017). There is no uniform training for SROs on how to work with youth and de-escalate school disruptions. Nor is there specialized training for working with immigrant youth, who face unique challenges (ACLU 2017). For example, newcomer students often have extensive trauma histories and frequently come from countries where the police are corrupt and untrustworthy, leading them to distrust SROs and school security guards. Prior trauma may lead students to act out disruptively, and a punitive response may escalate the situation further. It is common for trauma victims to experience more difficulty in punitive settings. SROs and security guards who do not understand the cultural and trauma histories of newcomer students may unfairly criminalize or stereotype them. Additionally, newcomer students may fear interacting with security staff, even when they themselves are victims of school violence. These conditions further marginalize vulnerable children, leading to even more violence against them. Racial bias also frames these interactions between police, security staff, and immigrant students. Students of color are more likely to be viewed by SROs and guards as acting criminally and more likely to be charged and arrested than their white peers (ACLU 2017). Consistently, there is no evidence that racial disparities in discipline are the consequence of “differences in rates or types of misbehavior” by students of color and white students (ACLU 2017). Ultimately, SROs and security guards may be more likely to see criminal conduct in what others might consider normal teenage or adolescent behavior, and they are more likely to unjustly criminalize the actions of immigrant youth based on implicit racial biases. Furthermore, as the Trump administration placed an increased emphasis on deporting alleged gang members or associates, new concerns about SROs and their relationship with local law enforcement arose with respect to surveillance of students and information sharing around gang investigations. For example, newcomer students may be wrongfully accused of gang affiliation because of their race, who they talk to at school, or even because of the clothing they wear (ILRC 2018). This unfair stereotyping and criminalization further marginalizes immigrant children and leads to even more violence against them, because they are unable to trust school security staff with their concerns about school violence. The result of all this is an intensifying criminalization of immigrant students, which can have far-reaching consequences for immigrant youth. When SROs get involved in school discipline, youth may end up being arrested or charged for behavior that otherwise would have been handled by school staff. Even a simple arrest can negatively impact an immigrant child: the arrest will become part of the youth’s record whether or not they are ultimately charged. If the youth is charged in delinquency or criminal proceedings and is adjudicated or convicted of an offense, this will negatively impact their ability to apply for immigration status, and may even completely bar them from obtaining immigration status or cause them to lose their current legal status and be deported. Thus, what may have started out as self-defense or as a minor incident in school (or no incident at all), may lead to dire consequences for immigrant youth, even though it could have been handled without the involvement of law enforcement (ILRC 2018). This risk of deportation makes immigrant students even less likely to report instances of school violence and will lead to even more school violence as a result.

In its worst iterations, this phenomenon of police criminalizing youth of color leads to physical violence against students, as documented by the ACLU (ACLU 2017). Additionally, SROs often wrongfully charge students with crimes for defending themselves against their aggressors, treating both victim and aggressor as criminals, as in Ana’s case (ACLU 2017). In the wake of Adam Toledo's tragic murder, Project Libertad remains committed to pursuing racial justice and equality for the students and families we work with, and we stand in solidarity with the family and loved ones of Adam Toledo in demanding justice for his murder. Project Libertad is a proud recipient of a corporate donation from the Sony Music Group Social Justice Fund.

FEBRUARY 1, 2021, PHOENIXVILLE, PA – Project Libertad is proud to announce a partnership with Sony Music Group, designed to support Project Libertad’s work with newcomer immigrant youth across Pennsylvania. Project Libertad is a proud recipient of a corporate donation from the Sony Music Group Social Justice Fund. This donation was made possible by the generosity of Sony Music Group, which has committed to aiding Project Libertad in its efforts to empower newcomer immigrant youth and their families by providing essential, youth-led and youth-centered legal and social services. Project Libertad envisions a world where all newcomer immigrant youth have access to the legal services, social services, academic support, and leadership opportunities needed to thrive. ESPAÑOL ABAJO PORTUGUÊS ABAIXO Here's what you need to know about President Biden's actions on immigration to date. Esto es lo que necesita saber sobre las acciones del presidente Biden sobre inmigración hasta la fecha. Aqui está o que você precisa saber sobre as ações do presidente Biden sobre a imigração até o momento. Aqui está o que você precisa saber sobre o projeto de lei de reforma da imigração proposto pelo presidente Biden! Esta postagem não tem como objetivo ser um conselho jurídico. Última atualização em 22/01/2021.

¡Esto es lo que usted necesita saber sobre el proyecto de ley de reforma migratoria propuesto por el presidente Biden! Esta publicación no pretende ser un consejo legal. Última actualización 22/1/2021.

Here's what you need to know about President Biden's proposed immigration reform bill! This post is not intended as legal advice. Last updated 1/22/2021.

|

AuthorSArchives

February 2024

Categories |

- Home

- About

- Donate

-

Programs

- Immigrant Children's Defense Project

- Know Your Rights Project

- Conexiones or Connections Therapy Program

- Legal-Mental Health Partnership

- Newcomer Support Programs

- RISE: Refugee and Immigrant Students Excelling

- Mentoring Program

- Juntos para Jóvenes: United for Youth

- Jóvenes Fuertes: Strong Youth

- Educator Trainings

- Adult ESL

- Scholarship

- Volunteer

- Media

- Contact

- Our Team

RSS Feed

RSS Feed